The Oakes Test

Also Known As: How Canada Decides Charter Questions

Canada is experiencing an election, in case you weren’t aware. You could be forgiven for not being aware, because even as Canadian elections go, this one is kind of low-key. It’s a snap election, called in the middle of a pandemic, and probably represents one of the most craven political moves of the last decade, and if polling is to be believed, it’s backfiring spectacularly. Our last election was in 2019, so this is a full two years early. There’s no functional reason to do this; the government didn’t face a confidence vote, they have a minority, but the NDP have been happy enough to prop them up and their mandate was relatively intact. There might be a political reason to call an election though; If you as PM think that for some reason, you might have an election problem in 2023, but you think you’ll be OK right now, you can call a snap election when the ground is more favorable to you, and kick the election after that to 2025 when the 2023 problem might be taken care of (I think this is a signal that Trudeau sees some economic issues coming down the pipe).

Without getting into the gritty of Canadian politics, the election is looking to be a disaster for Trudeau. Even if the Liberals win the most seats, the likelihood based on polls right now is that he’ll form another minority government and have to compromise with someone else, probably the NDP again, but there’s a good chance Erin O’Toole’s Conservatives are able to pull in the most seats. They have the highest polling support right now, and their support is more healthily distributed than it was in 2019. The alternative to all this was not calling a snap election in the middle of a pandemic and continuing their mandate for at least the next two years.

This is all tangential to my point, I just find it kind of funny. The real topic stems from the leader of one of the smaller parties, the PPC, Maxime Bernier, who is fairly famously unvaccinated and shirking all kinds of Covid restrictions across Canada in a strategy that revolves around tossing red meat to his base and getting lots of free publicity. This has resulted in conversations, and I was asked the question, “What happened to our Rights?”

It’s a good question.

What is Oakes?

Basically, a test based on a 1986 case that gives guidance to what a government can and cannot do in the context of abridging Charter rights.

What Was The Case?

R v. Oakes. The RCMP caught Oakes with a substantial amount of hash oil and cash, which I will refer to as “hashncash” if I ever mention this again. Following their investigation, they charged him with possession for the purpose of trafficking under the Narcotic Control Act (NCA). Oakes claimed that the drugs were his own and that he did not intend to sell them, which would still be illegal, but the penalties for possession are much, much lighter than the penalties for trafficking. At that time, under Section 8 of the NCA, anyone found with illegal drugs was presumed guilty of trafficking, and it was up to the accused to prove that they was not guilty (This is similar to all those bullshit civil forfeiture cases in America.).

Oakes challenged Section 8 of the NCA, arguing that it violated the presumption of innocence guaranteed by section 11(d) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The Supreme Court of Canada unanimously found that Oakes’ rights had been violated.

Section 1 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms states that “The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees the rights and freedoms set out in it subject only to such reasonable limits prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society.” To wit: Our rights are not suicide pacts, but if the government wants to infringe on those rights, they need a damn good reason to do so. Previous to Oakes, what constituted a “damn good reason” wasn’t clear, and so the test was born.

What is The Test?

A two-step balancing test to determine whether the government can justify a law which limits a Charter right.

The First Step is that the government must establish that purpose of the law is both “pressing and substantial”. Governments are usually successful at this step, because it doesn’t take much imagination to come up with a connection between what they’re doing and the rule they’re trying to enforce. Really… This Step only stops the most egregious of government idiocy.

In a current context, almost all of the lockdown measures infringe on Charter rights, some of the more obvious being Section 6(2)(a) (Mobility and travel between provinces) and Section 2(b, c, d) (Freedoms of Expression, Assembly, and Association). In order to satisfy the first test, the government merely has to say, “We’re in a Pandemic, yo!”

The Second Step is more involved. It’s a proportionality analysis using three sub-tests;

A) The government must establish that their proposed rule is rationally connected to the purpose of the law. It’s similar but different to step one; Step one requires that the law have an identifiable need that needs to be addressed, Step 2a requires some logic connecting the proposed legislation actually be related to that need. “We’re in a pandemic” is a need, “so we’re going to limit interprovincial travel” addresses that need, but “so we’re going to make French the sole official Canadian language” does not.

B) Then the government must “minimally impair” the violated right. “A provision that limits a Charter right will be constitutional only if it impairs the Charter right as little as possible or is “within a range of reasonably supportable alternatives.”

This is a big one. Basically… If there’s a reasonable alternative to deal with the need without infringing on the right, the infringement on the right is not constitutional, and if there is no alternative, then the government must endeavor to infringe on the rights as little as possible in order to satisfy the need.

C) Then the court examines the law’s “proportionate effects”. Basically, even if the government can satisfy all the steps above: They’ve identified a need, tied an action to that need, and attempted to act in a way that minimizes impact on our rights, the court can still determine that the infringement might be too high a price to pay to advance the government’s purpose.

That’s All Well And Good, But How Often Does the Government Prevail Anyway?

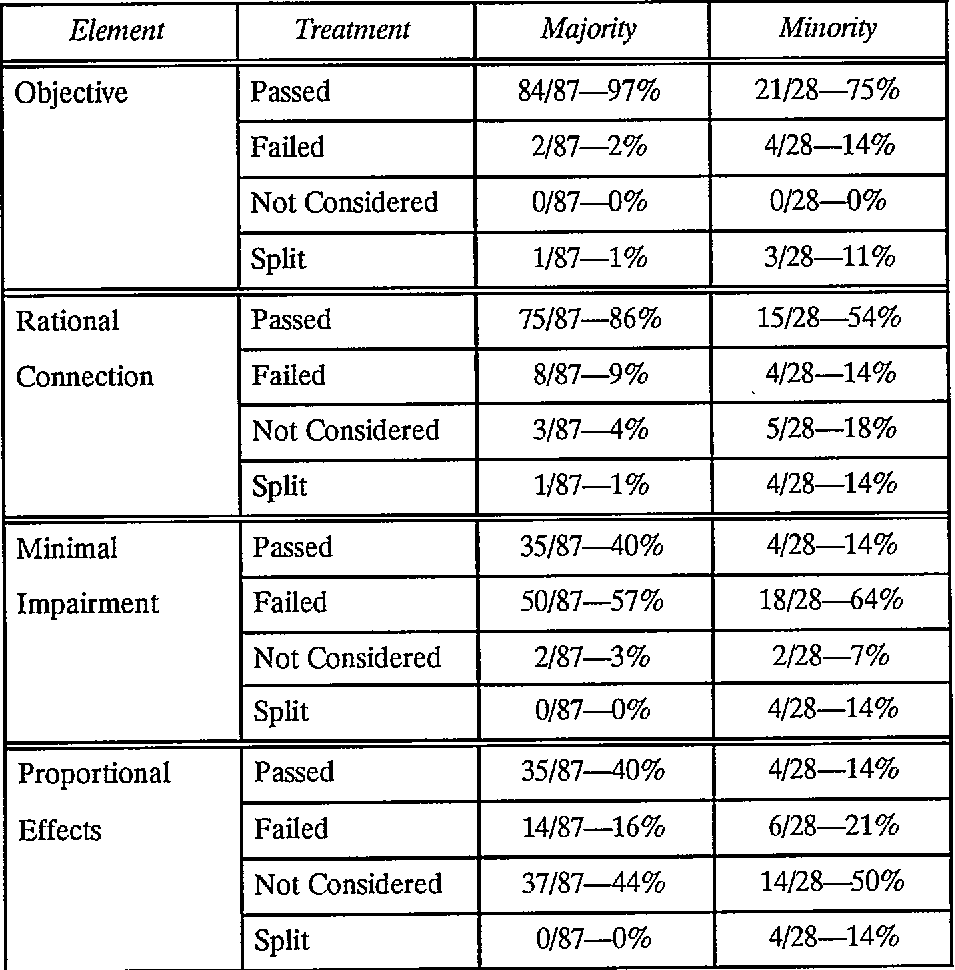

Less than half the time, I’m going to put a chart below this that breaks this down, but basically, if a decision decides that the government fails the Oakes test at any stage of the test, it ultimately fails. This means that any test could fail in all four areas, and they’ll consider all of them even if one obviously fails, so there’s bound to be some double counting in the numbers, but the important line is the failure rate for minimal impairment, where the government has failed to pass the Oakes test in at least 57% of instances where it was applied. That’s the lower limit for failures.

What does that mean for our Rights?

Specifically in the context of Covid restrictions? Specifically in the context of Manitoba restrictions, which I am most familiar with? I think the government is going to have an absolutely awful time proving minimal impairment, and is going to end up writing off most, if not all, of their Covid enforcement citations. I’m not sure whether the Pallister government overestimated their power, or whether they knew that they were going to rip them up all along, but wanted temporary compliance from law-abiding Manitobans, but 10% of Manitoba’s Covid citations have been paid, and it’s only a matter of time before the others make it through the courts. And it’s my expectation that that logic will probably apply to most of the other provinces to some degree or another.